What can be more magical than seeing images of something familiar move before your eyes? Or capturing a moment in time and reliving it over and over again? For many of us born in the 20th century and beyond, we undoubtedly take motion pictures for granted. Whether we grew up in front of the television or with our eyes glued to our smartphones, motion pictures have become an integral part of our culture. These days, it's not enough to simply appreciate the day-to-day moments we find interesting, but now must also record them onto our mobile phones to share on social media. What was once considered an entire television studio now fit in the palm of your hand. But it wasn’t too long ago where such a possibility was only a pipe dream - a science-fiction fantasy.

Before the invention of celluloid film or even photographic paper, we’ve been able to produce the illusion of motion. Although we’re here to discuss the early history of motion picture in the home rather than the broad history of motion picture itself, it's interesting to note that the history of cinema began in the home, having evolved from the magic lantern and perhaps more importantly, the optical toys of the early 1830s. These were devices sold to children which simulated motion by exploiting a brain phenomena known as the persistence of motion. Although these images were more like animations than moving photographs, they nonetheless introduced motion pictures into the home. It would take another seventy years for these toys to evolve into the motion picture movie projectors we think of today. And from there, another 25 of experimentation and invention for those projectors to pick up momentum in the domestic market.

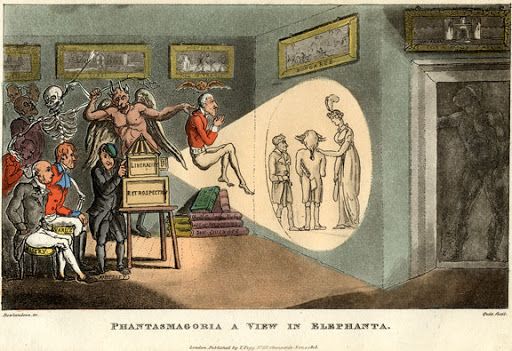

We can trace the lineage of the motion picture projector all the way back to the mid-1600s with the development of the magic lantern. Using the principles of the camera obscura, the device worked by using light and lenses to project images onto walls. These images were usually painted onto glass slides, which were then placed between the light source and the lens. The first magic lantern is believed to have been invented by Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens, who in his later years, would express embarrassment over having invented it, calling it “frivolous.” It wasn’t until Thomas Walgensten, an associate of Huygens, discovered its commercial potential was the device mass produced and sold throughout Europe, and later the world. Over the centuries, it would become a popular entertainment device used by children, educators and entertainers alike. In fact, magic lantern shows could be considered the earliest predecessor to the movie theater experience, as showman would use the devices to tell stories to large audiences in an auditorium. Stage magicians especially benefited from the effects of the lantern, using it to create ghostly projections of demons and spirits.

Despite the lantern’s popularity as an entertainment device for the home, there had never been a mass-produced version that projected motion pictures. Instead, mechanical slides were developed that would produce transitions or make aspects of a single slide move. For instance, making the waves below a ship move or having a mouse jump into a sleeping man’s mouth (actual examples from the day). Although inventors would eventually come up with motion picture versions, it would not be until a new toy hit the scene, a toy which got everything into motion - the phenakistoscope.

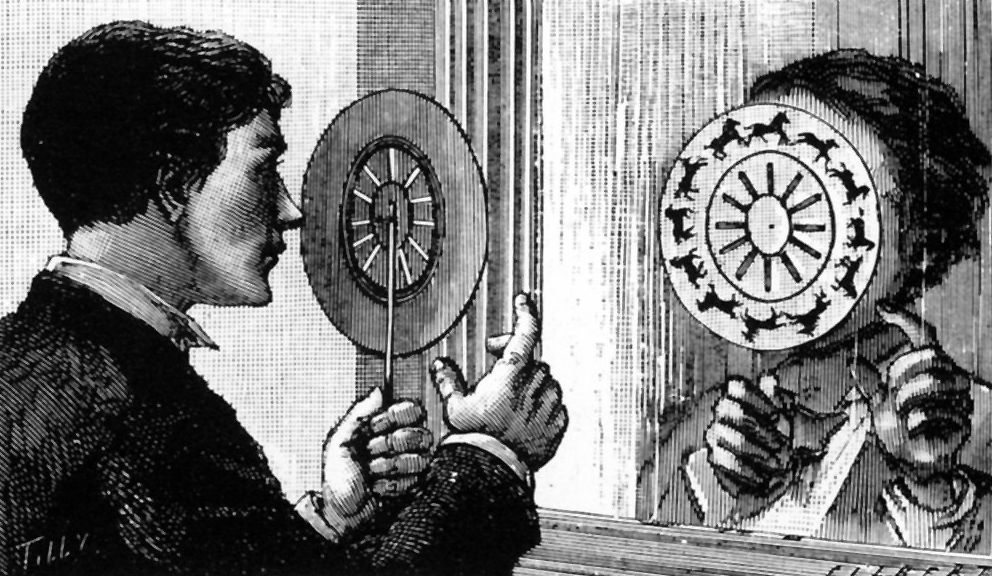

Invented in 1832, the phenakistoscope is believed to have been invented by two individuals working separately in the same month - Belgium scientist Joseph Plateau and Austrian professor Simon Stampfer. Both had been studying optical illusions, having been inspired by other scientists who had been studying the optical illusions produced by a spinning wheel. The device is a paper disk with illustrations around its edge. Each image is in a single phase of motion, and between them, are vertical slots. When the disk is quickly spun on a vertical handle, the person holding it could look through the slots and see an animated figure reflected onto a mirror. The device would remain a popular toy for the next 35 years, with many manufacturers creating their own spinning disk toys, calling them by different names.

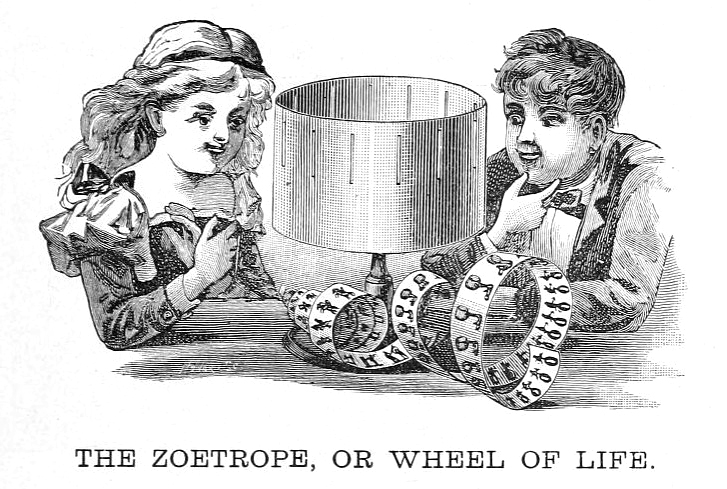

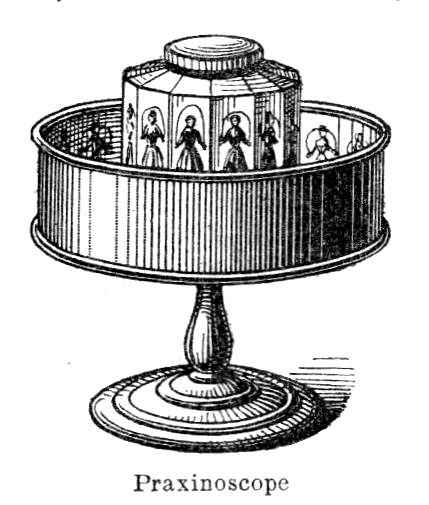

In 1833, the zoetrope expanded on the phenakistoscope by placing each phase of motion onto the inside walls of a cylinder with slots, eliminating the need for a mirror mounted to a wall. The use of a cylinder was first suggested by Stampfer, but was first demonstrated by William Horner in 1834. Over thirty years later in 1865, Milton Bradley began to mass produce a perfected zoetrope, and it soon replaced the phenakistoscope as the quintessential animation toy. It was improved upon even further by Charles-Émile Reynaud in 1877 with the praxinoscope, which placed mirrors in the center of the cylinder, removing the need to view the animation through the slots. The person using the device would simply look into the cylinder from above to see the desired effect reflected onto the mirrors inside.

Although the phenakistoscope had been replaced in the market, inventors weren’t finished with it just yet. They were still developing ways to combine it (and in at least one case, the praxinoscope) with the magic lantern to create the first motion picture projections. These prototypes would culminate in Edward Muybridge’s famous Zoopraxiscope in 1880 (pictured below), a device that projected animated plants and animals from painted glass disks. At its first demonstration, it was reported that: “What attracted the most attention - in fact, aroused a pronounced flutter of enthusiasm from the audience, was the representation, by aid of the Zoogyroscope (later called Zoopraxiscope), of horses in motion. While the previous views had shown their positions at different stages of motion, these placed upon the screen, apparently, the living, moving horse.” Although none of these projected versions were mass produced for the public, the Zoopraxiscope is believed by some historians to have inspired one inventor to create a device that takes a large step closer to the first domestic movie projector.

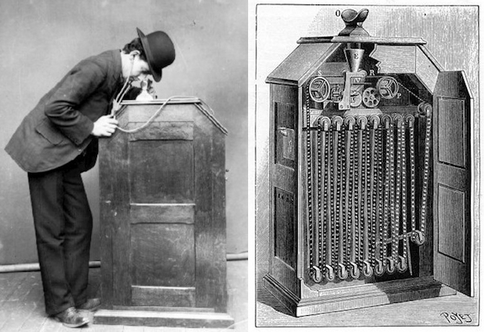

Developed in 1891 by Edison, the original Kinetoscope (pictured below) was a peephole device that illuminated moving images on a 35mm film strip using a light and high speed shutter. Originally conceived as a commercial device, the first Kinetoscope parlor opened on a New York City corner in 1894. Inside were two rows of the machines with each playing a different loop, and for 50 cents (a large fee at the time) you can view them all. Although the device was successful, it was short lived as other inventors, such as Charles Francis Jenkins, were inventing new and more innovative ways to project motion pictures. Jenkin’s Phantoscope proved more profits could be made by entertaining an entire audience at once. Edison responded in 1895, when his team began development on a projecting version of the Kinetoscope.

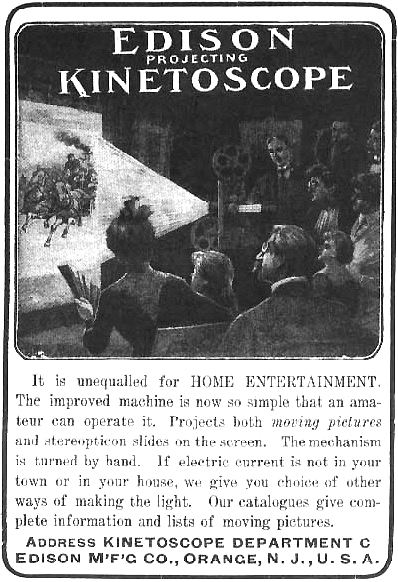

Aptly named the Projecting Kinetoscope, it was first demonstrated in 1896 to a roaring crowd. A writer in attendance described the audience response: “So enthusiastic was the appreciation of the crowd long before this extraordinary exhibition was finished that vociferous cheering was heard.” Initially marketed towards theater owners and roadshow men, the device would first hit the market in 1897. Also available were catalogs where its owner could purchase a variety of printed films to exhibit to their audiences.

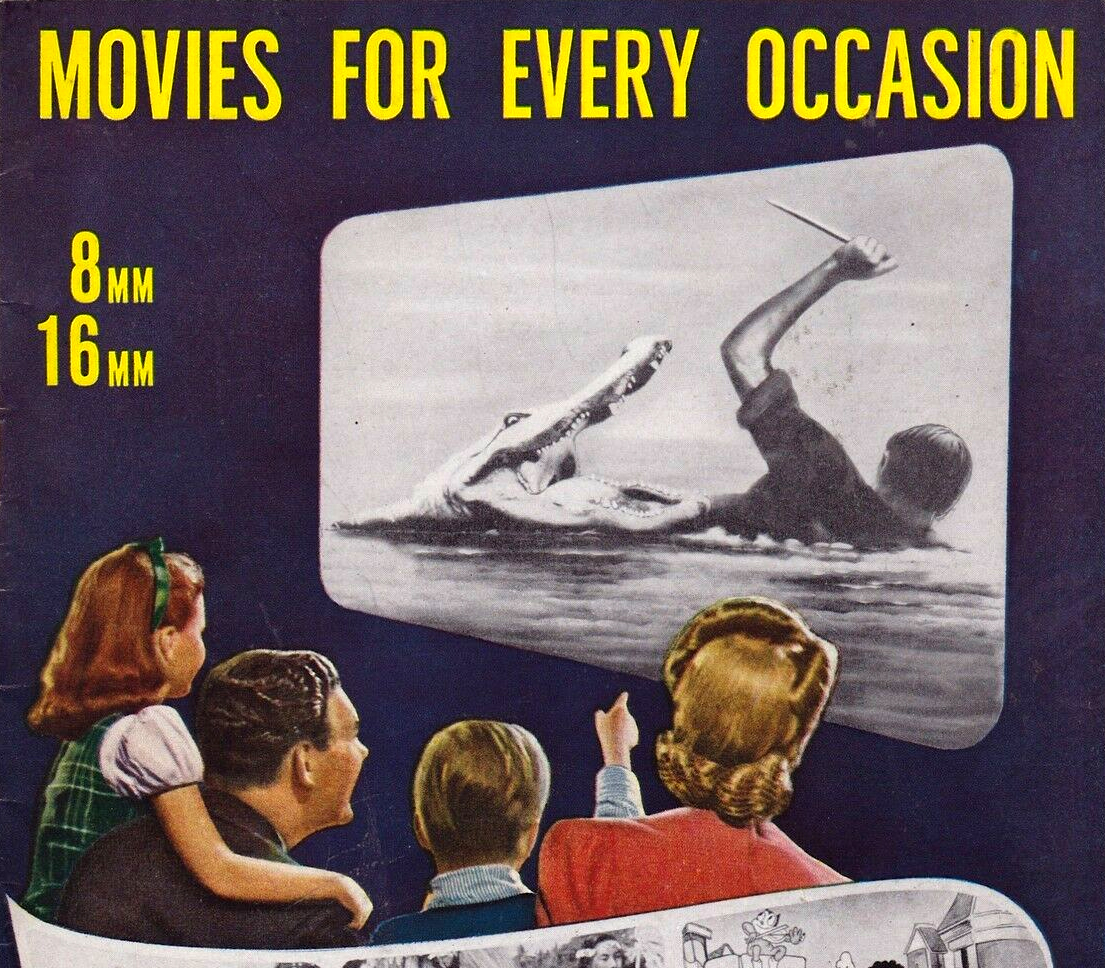

At the same time, lantern makers were developing magic lantern attachments intended to project 35mm motion pictures in the home for the first time. Among the very first of these is the Watson & Sons Motorgraph. In an advert from 1897 (pictured above - left), it states boldly along the top “Animated Photographs At Home” and below it, touts a catalog of over 1000 subjects. Other small manufacturers also took a stab at the home projector market, but none had any staying power, with most dismissed as dangerous toys by industry professionals. Edison might be considered the first major manufacturer to market a projector for the home, as the company began advertising their Projecting Kinetoscope for domestic use in magazines during the 1900s. In one such advertisement (picture above - right), a family is depicted in a dark living room, all huddled around a motion picture screen. Below the image, reads “unequalled for home entertainment.” Of course, this was just a cheap attempt to cross market the projector despite being poorly suited for the domestic market. It still relied on 35mm nitrate film - a combustible stock that was far too dangerous to be brought into a home. If Edison was to market a projector for the domestic market, something had to change.

Meanwhile, as Edison, Pathe and the Lumiere brothers were perfecting their projection technologies, a new motion picture device is launched to the public in 1900. Based on the technology of the Mutoscope (a device similar to Edison's Kinetoscope but used a "flip book" technology as opposed to illuminated film), the Kinora (pictured above) was a tabletop device intended for the home that used reels of photographs printed onto cards. When cranked, it would flip through the cards, showing approximately 30 seconds of motion picture. Originally invented by the Lumiere brothers in 1895, they sold the patent to Gaumont so they could focus on the development of their Cinematograph. Gaumont released the device with 100 different reels in 1900, and in 1902, The British Mutoscope & Biograph Company released their version in the UK. In many ways, the Kinora was the first practical and safe motion picture device for the home. The last of them were sold in 1914, after a fire had destroyed a British manufacturing facility. By that point, public interest in the Kinora had already ran its course, as it was being replaced by improved home projectors.

In Part II, we will delve into the first practical and safe motion picture projectors made specifically for the home. Stay tuned!

Comments 0

Login / Register to post comments