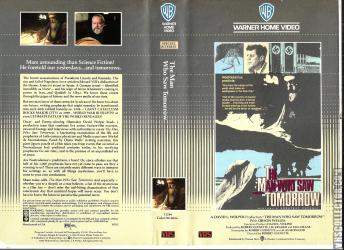

The Man Who Saw Tomorrow

Catalog Number

11246

-

Primary Distributor (If not listed, select "OTHER")

Catalog Number

11246

Primary Distributor (If not listed, select "OTHER")

Release Year

Country

N/A (NTSC)

N/A | N/A | N/A

N/A | N/A

The Man Who Saw Tomorrow (1981)

Additional Information

Additional Information

HistThe Man who Saw Tomorrow is none other than Michel de Nostradamus, the French doctor who lived in the 16th century but supposedly saw far ahead into the 20th century and beyond. This documentary is an attempt to bring home the interpretation of some of his predictions using historical footage, newsreels, interviews, and dramatized scenes. The film is narrated by Orson Welles -- shown sitting in a small, nondescript office, with the voice of Nostradamus provided by Philip L. Clarke. Predictions noted in the documentary include Napoleon's career, the coming of Hitler, and of Franco, and events across the sea: the assassinations of Lincoln and Kennedy, and a supposed nuclear attack on New York City in 1999, among other dire events. If equal time had been given to scholars to refute the glib interpretations by illustrating how abstruse and confusing the original 16th-century French quatrains really are, the documentary might have achieved more balance. ory's greatest psychic.

The Man Who Saw Tomorrow is a 1981 documentary-style movie about the predictions of French astrologer and physician Michel de Notredame (Nostradamus).

The Man Who Saw Tomorrow is narrated (one might say "hosted") by Orson Welles. The film depicts many of Nostradamus' prediction historical evidence of Nostradamus' predicting ability, though as with other works, nothing is offered which conclusively proves his accuracy. The last quarter of the film discusses his (relatively dark) translated predictions for (at the time) the next millennium. In particular, as may be expected with Hollywood films, the subject matter seems rather slanted to the projections that affect the United States and its allies directly at the time of the film's inception. As with most Nostradamus publications, there are no scientifically testable predictions directly included in this film, only suggestions and allusions.

The film does not discuss important topics that trouble scholars to this day about Nostradamus: Were his writings predictions of the distant future or descriptions of then current events? Was he intentionally predicting the future, or simply extrapolating? The film presents Nostradamus as a scholar and acknowledged "seer", which is certainly not accepted to have been the case in his own time, much less now. Several historical examples of his apparent predicting ability are cited, all of which (necessarily) take the form of hearsay owing to the era from which they are drawn.

An example of this is the treatise, familiar to Nostradamus readers, surrounding the prediction at the feast of a wealthy farmer: Nostradamus is asked which of two pigs the dinner guests will eat that night. He is alleged to have replied "the black pig". The farmer then sent word that the white pig was to be butchered and cooked for the evenings' feast. During the feast, the farmer is reported to have summoned his butcher/cook again and demanded to know which pig they had eaten. The cook replied that he had killed the white pig, as ordered, but that in a moment of inattention, he had allowed the farm dogs to drag off the carcass. Thus, as Nostradamus had allegedly predicted, he had been forced to kill the black pig as well and serve it in place of the white.

Welles, though he agreed to host the film, was not a believer in the subject matter presented. Welles' main objection to the generally accepted translations of Nostradamus' quatrains (so called because Nostradamus organized all his works into a series of four lined prose, which were then collected into "centuries", or groups of 100 such works) relates in part to the translation efforts. While many skilled linguists have worked on the problem of translating the works of Nostradamus, all have struggled with the format the author used.

Nostradamus lived and wrote during a period of political and religious censorship. Because of this it is said he disguised his writings not only with somewhat cryptic language, but in four different languages (Latin, French, Italian and Greek). Not content with such obfuscation, Nostradamus is also said to have used anagrams to further confuse potential inquisitors (particularly with respect to names and places).

Welles himself completely rejected the central theme of the film after having made it. It is not known if Welles was contractually obligated to narrate the film, or if he simply grew disenchanted with its subject matter and presentation after completing it. Perhaps Welles' most public detraction from the subject matter of the film occurred during a guest appearance on an early 1980s episode of The Merv Griffin Show; "One might as well make predictions based on random passages from the phone book", he offered when asked about the film, before moving on to discuss other projects more interesting to him personally.

It is worth noting that Welles has previously been known, despite his grand and well-deserved reputation as a performer, to take the equivalent of film "grunt work" in order to self-finance his personal projects. In and around the time of this film's creation, Welles was attempting to finance a restored release (which would today be referred to as a "director's cut") of his film The Magnificent Ambersons, which he had always claimed the studio ruined during editing.

Release Date: January 1981

Distrib: Warner Brothers

The Man Who Saw Tomorrow is a 1981 documentary-style movie about the predictions of French astrologer and physician Michel de Notredame (Nostradamus).

The Man Who Saw Tomorrow is narrated (one might say "hosted") by Orson Welles. The film depicts many of Nostradamus' prediction historical evidence of Nostradamus' predicting ability, though as with other works, nothing is offered which conclusively proves his accuracy. The last quarter of the film discusses his (relatively dark) translated predictions for (at the time) the next millennium. In particular, as may be expected with Hollywood films, the subject matter seems rather slanted to the projections that affect the United States and its allies directly at the time of the film's inception. As with most Nostradamus publications, there are no scientifically testable predictions directly included in this film, only suggestions and allusions.

The film does not discuss important topics that trouble scholars to this day about Nostradamus: Were his writings predictions of the distant future or descriptions of then current events? Was he intentionally predicting the future, or simply extrapolating? The film presents Nostradamus as a scholar and acknowledged "seer", which is certainly not accepted to have been the case in his own time, much less now. Several historical examples of his apparent predicting ability are cited, all of which (necessarily) take the form of hearsay owing to the era from which they are drawn.

An example of this is the treatise, familiar to Nostradamus readers, surrounding the prediction at the feast of a wealthy farmer: Nostradamus is asked which of two pigs the dinner guests will eat that night. He is alleged to have replied "the black pig". The farmer then sent word that the white pig was to be butchered and cooked for the evenings' feast. During the feast, the farmer is reported to have summoned his butcher/cook again and demanded to know which pig they had eaten. The cook replied that he had killed the white pig, as ordered, but that in a moment of inattention, he had allowed the farm dogs to drag off the carcass. Thus, as Nostradamus had allegedly predicted, he had been forced to kill the black pig as well and serve it in place of the white.

Welles, though he agreed to host the film, was not a believer in the subject matter presented. Welles' main objection to the generally accepted translations of Nostradamus' quatrains (so called because Nostradamus organized all his works into a series of four lined prose, which were then collected into "centuries", or groups of 100 such works) relates in part to the translation efforts. While many skilled linguists have worked on the problem of translating the works of Nostradamus, all have struggled with the format the author used.

Nostradamus lived and wrote during a period of political and religious censorship. Because of this it is said he disguised his writings not only with somewhat cryptic language, but in four different languages (Latin, French, Italian and Greek). Not content with such obfuscation, Nostradamus is also said to have used anagrams to further confuse potential inquisitors (particularly with respect to names and places).

Welles himself completely rejected the central theme of the film after having made it. It is not known if Welles was contractually obligated to narrate the film, or if he simply grew disenchanted with its subject matter and presentation after completing it. Perhaps Welles' most public detraction from the subject matter of the film occurred during a guest appearance on an early 1980s episode of The Merv Griffin Show; "One might as well make predictions based on random passages from the phone book", he offered when asked about the film, before moving on to discuss other projects more interesting to him personally.

It is worth noting that Welles has previously been known, despite his grand and well-deserved reputation as a performer, to take the equivalent of film "grunt work" in order to self-finance his personal projects. In and around the time of this film's creation, Welles was attempting to finance a restored release (which would today be referred to as a "director's cut") of his film The Magnificent Ambersons, which he had always claimed the studio ruined during editing.

Release Date: January 1981

Distrib: Warner Brothers

Related Links

Related Releases1

Catalog Number

11246

Primary Distributor (If not listed, select "OTHER")

The Man Who Saw Tomorrow (1981)

Release Year

Catalog Number

11246

Primary Distributor (If not listed, select "OTHER")

Catalog Number

11246

Comments0

Login / Register to post comments