“He pioneered in the home movies market, establishing a global distribution system.”

-Variety (1960)

When most historians refer to the early years of home video, they often credit Andre Blay as its founder. His deal to license 50 films from 20th Century Fox in 1977 inspired many others to follow suit. Although Blay was not the first to sell pre-recorded content on video cassettes (Cartrivision had experimented with the venture several years earlier), he was in fact the first to have massive success with it. Blay, in my opinion, wasn’t so much an innovator, as he was an entrepreneur in the right place at the right time, and with the access to the right technology. So if Blay isn’t responsible for bringing pre-recorded movies into the home for the first time, who is?

This was made possible decades before Andre Blay, in the form of printed films (these are reels of film sold or rented with content already on them). Its difficult to first imagine these as part of the home video market. Some might even argue that these films don’t fall under the “home video” banner since they’re technically not a video format. But this is just semantics. “Home video” is an umbrella term used to describe any pre-recorded motion picture media intended for home use. It's similar to how we still use the term “film” to describe movies that were shot on video. These just happen to be the terms that have stuck over the years. So with this understood, printed films (or "home movies" as they were called at the time) are of the home video family.

Although printed films were made available to the public as early as 1900, Castle gave them mass appeal with their low cost and accessibility. Often advertised as costing less than undeveloped film, they found a new market among the growing middle-class. No longer were home movies a niche market for the elite, confined to manufacturer catalogs, specialty camera shops or exclusive film libraries. They were now found in thousands of retail shops across the country, including supermarkets, department stores and even the local drug store.

Castle also influenced the budding home movies industry with his clever marketing. He enticed consumers to visit distant lands with his travelogue series in full-page magazine ads. He lured curious shoppers with attractive packaging unique to each film. Prior to Castle, most printed films were packaged in generic boxes with printed labels. Castle’s packaging on the other hand, were vibrant and colorful, hinting at the adventures or laughs that await inside. Castle made selling these movies an industry of its own, and for this reason, I credit him as the true father of home video. Now let us jump into Eugene Castle’s timeline. Although shorter in comparison to later pioneers, he is no less important.

Castle’s career in home movies began when he became a cameraman and editor for Pathe News in the 1910s. It is here where he became proficient in his craft. In 1918, he became a distributor himself, the first to specialize in educational and industrial films. During the post-war years of the 1920’s, the United States saw rapid economic growth and prosperity. As the country became the wealthiest in the world, middle-class Americans began indulging in products once considered luxuries for the wealthy - cars, radios, and of course, the portable projector. Movie palaces also saw rapid growth with the introduction of sound cinema, eventually replacing the vaudeville circuit.

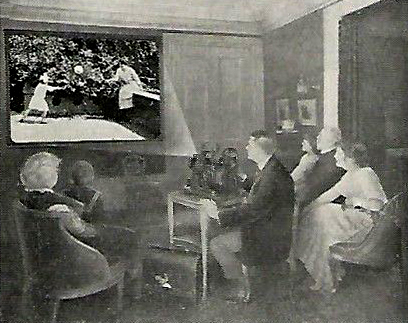

In September 1927 following a city wide strike of theater operators in Chicago, Billboard reported that, “hundreds of film addicts sought to overcome their temporary discomfiture by resorting to parlor movies. Dealers in portable projection machines and rented films reported a circulating list of some 2,000 customers, indicating the possession of at least that many home projection machines.” Catching wind of the increased use of home projectors, Pathe finally put a campaign into full gear to revive their portable projector, the Pathescope, in the U.S.

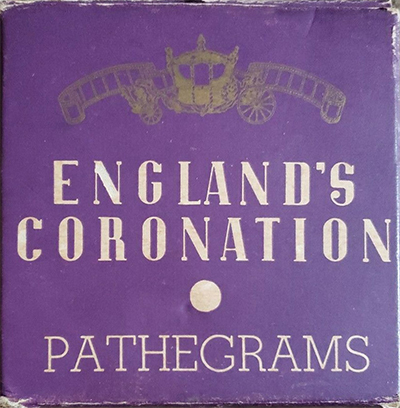

Later that same year, Billboard announced that “Pathe has pictures ready for home use.” They’re short 16mm subjects, which they call Pathegrams. According to the article, “Pathe believes there is a tremendous field in home exhibition of films and that movie enthusiasts will make ready use of the new library prepared for the smaller pictures.” These early films are mostly educational with a few Hal Roach comedies. Although more of the public owned home projectors than ever before, these films weren’t cheap by any means. A 400ft film of The Little Indian Weaver retailed at $35, or approximately $500 in 2019. Many resorted to renting the reels from the few film libraries that existed in or around major cities. Eventually, interest in Pathegrams waned with the onset of the Great Depression, and as a result, Pathe’s home movie division was abandoned.

As the economy improved, more homes became electrified, thus renewing an interest in portable projectors. Jumping on the opportunity, Eugene Castle and Pathe collaborate to resurrect the Pathegrams home movie division in 1937. Castle then compiled, edited and distributed three films himself with little input from Pathe. The first, Hindenburg Explodes!, is a tremendous success taking in a reported $40,000-$50,000 in the first few days, making it the very first home video hit. Variety attributed these estimates to “the fact that this is probably the first time such an outstanding news event has been made available to the public so soon after the occurrence.” The two follow up films - The Coronation of Their Majesties King George VI and Queen Elizabeth and The Life of Edward - Britain’s Ex-King also fare very well, selling in over 18,000 locations across the country, costing between $5.50 (approx. $95 in 2018) and $22.50 (approx. $390 in 2018).

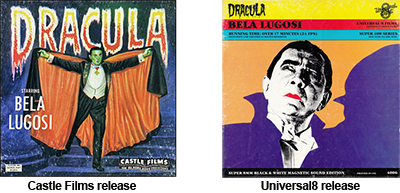

The success of these first three films on the revived Pathegrams label inspired Castle to split with Pathe to produce and distribute his own home movies through his distribution company, Castle Films. He made it official in July of 1937, when he publicly announced his plan to release home movies. According to The New York Times, Castle “has the distinction of being the first on record to introduce newsreels on 8 and 16mm stock for projection in the home. He got the idea about a year ago, after keeping a close watch on the mounting sales figures of home movie projectors.” In actuality, Castle was not the first to distribute newsreels on the home market, but because he pushed them hard in 1937, it was the first time much of the country became aware of home movies. By the end of year, Castle Films had 12 home movies on the market, which include newsreels, silent movies, and sports films. The newsreels are especially popular, expanding into a series of films Castle called News Parade. Released annually, these highlight the top headlines of the year. They’re such a hit, that he expands the series with specialty versions, such as The World Parade, The Adventure Parade and The Sports Parade. With an approximate running time of 9-12 minutes on a single reel, they’re soon dubbed “one-reelers” by collectors.

In 1941, Castle Films won a bid to print, promote and distribute between 12,000-15,000 16mm educational films for the U.S. Government. Later that year, Japan bombs Pearl Harbor and the U.S. enters World War 2. The American public, eager to witness the events unfolding in Europe, flocked to movie houses to view the latest wartime footage. Castle seized the opportunity, and distributed his own home movie versions - 37 in total. These introduced home movies to an even wider audience. The New York Times, in reporting on Castle’s success in 1943, stated that “Mr. Castle estimates that in one way or another, his films reach a public of not less than 20,000,000… if one were to gather together all the prints of a current item it would about fill Yankee Stadium twice.”

With this increasing popularity of home movies and Castle’s success, major studios began to notice. Pathe, once collaborating with Castle Films, bought out two of the company’s competitors, Official Films and Pictorial Films. In January 1947, Universal’s non-theatrical branch, United World Films, purchased a controlling interest in Castle Films, eventually buying Eugene Castle out a few years later for a reported total of $3,000,000. He becomes an investment counsellor shortly thereafter, before retiring in his early 50s. During these years, he became an outspoken critic of “American overseas information operations,” and writes two politically charged books accusing the U.S. government of wasting tax dollars on foreign aid. When he dies in 1960 due to surgery complications, Variety reported that “he pioneered in the home movies market, establishing a global distribution system.”

Universal’s purchase of Castle Films was the studio’s first foray into what would later be called “home video.” They continued the Castle Films brand up until 1977, when they conducted a complete overhaul of their home movie division. The name was changed to Universal 8 and each release began to include two reels with some housed in a more durable clamshell case. Universal 8 only lasted three years before passing the torch to the next generation of home media - the burgeoning videocassette.

Thirty years before Andre Blay made a videocassette distribution deal with 20th Century Fox, movies for the home were already being marketed in adverts, given colorful packaging and made available for sale or rent with tremendous success. The industry Blay thought he created in 1977 was already established by Eugene Castle decades earlier. The only difference was that the VCR kicked off a revolution with its ease of use and recording capability. But when the dust finally settled, the world had forgotten those who carried them to that point. In particular, our friend Eugene W. Castle. Rest in peace.

References:

-

When the Cock Crows: A History of Pathe Exchange by Richard Lewis Ward

-

Castle Films: A Hobbyist’s Guide by Scott MacGillivray

-

Pathe Has Pictures Ready for Home Use

Billboard; Nov 12, 1927; pg. 39, 46 -

Hindenburg Crash Footage Success

Variety; May 19, 1937; pg. 11 -

Of One Man’s Castle: In Which Eugene Castle Proves That Big Profits Can Grow on Small

New York Times; Apr 4, 1943; pg. X3 -

Eugene W. Castle Dies At 62; Film Producer Fought U.S. 'Propaganda' Landry

Variety; Feb 10, 1960; pg. 4 -

Newsreels for the Home

New York Times; Jul 4, 1937; pg. 4X

Comments 2

Login / Register to post comments